- Best Mutual Funds: As deadline to submit proof of investment looms, these 10 ELSS funds gave highest return to investors

- That’s a wrap for 2024

- Lazard International Strategic Equity Portfolio Q3 2024 Commentary (Mutual Fund:LISIX)

- Fidelity Investments Canada ULC Announces Estimated 2024 Annual Reinvested Capital Gains Distributions for Fidelity ETFs and ETF Series of Fidelity Mutual Funds Français

- Balancing Core & Satellite Funds

Active management has taken exchange-traded funds by storm. Once an oxymoron, given passive ETFs’ dominance, active ETFs have brought in 27% of new money invested in ETFs so far this year, and their share of US ETF assets has risen above 8%.

Bạn đang xem: How to Find the Right Active ETF for Your Portfolio

In many ways, this was precipitated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s passage of the “ETF Rule” in 2019. Rule 6c-11 gave more flexibility to portfolio managers and made it easier to bring ETFs to market. Custom creation and redemption baskets further enhanced an already tax-efficient wrapper.

The benefits became too great to ignore for some managers. Those who quickly adopted ETFs after the ETF Rule was passed caught the trend early and rapidly climbed the active ETF leaderboard.

ETF holdouts were generally met with outflows from their mutual funds, while competing ETFs grew. One by one, traditional mutual fund managers began launching or converting mutual funds into their first ETFs, with mixed results.

Traditional active managers soon discovered that not every strategy makes sense as an ETF. And getting ETFs into investors’ portfolios is a distinct game from mutual funds. The days of commissioned distribution are fleeting. Fund companies have less control over getting their strategies into investors’ hands.

As a result, the active ETF landscape developed differently from its mutual fund cousins. For example, options-based ETFs have jumped into retail and advisor-built portfolios, while multi-asset ETFs are nearly absent. Most of the money flowing into ETFs has gone toward those that don’t deviate too far from the market, meaning ETF investors’ adoption of active management is only a half-step from their passive roots. For ETFs, low cost remains king.

These are not your parents’ active strategies. Small portfolios built by high-fee stock-pickers remain niche in the ETF market. Evolving investor and advisor tastes are partly to blame. But ETFs just aren’t ideal for some active strategies.

This is the active ETF paradox: Markets where active ETFs make the most sense often conflict with where active managers can add the most value.

Active Versus Passive

Unlike mutual funds, ETFs can’t close to new investors. A flood of new money could compromise a strategy’s ability to outperform. Large-cap stocks and Treasuries have the highest capacity, meaning a fund holding them should have room to manage large amounts of money without running its edge. That makes those asset classes a good fit for ETFs.

However, smaller markets are most prone to capacity risk. Concentrated portfolios of small-cap or emerging-markets stocks are not ideal for an ETF. But active managers have the most alpha potential in these types of markets because of their inefficiencies and informational asymmetries.

Xem thêm : Databricks nears 9.5 billion mega-investment

Our Active/Passive Barometer demonstrates these long-term trends. Just over 10% of US large-cap active managers beat the average passive fund over the decade through 2023. Managers found more success in small caps, foreign markets, real estate, and bonds.

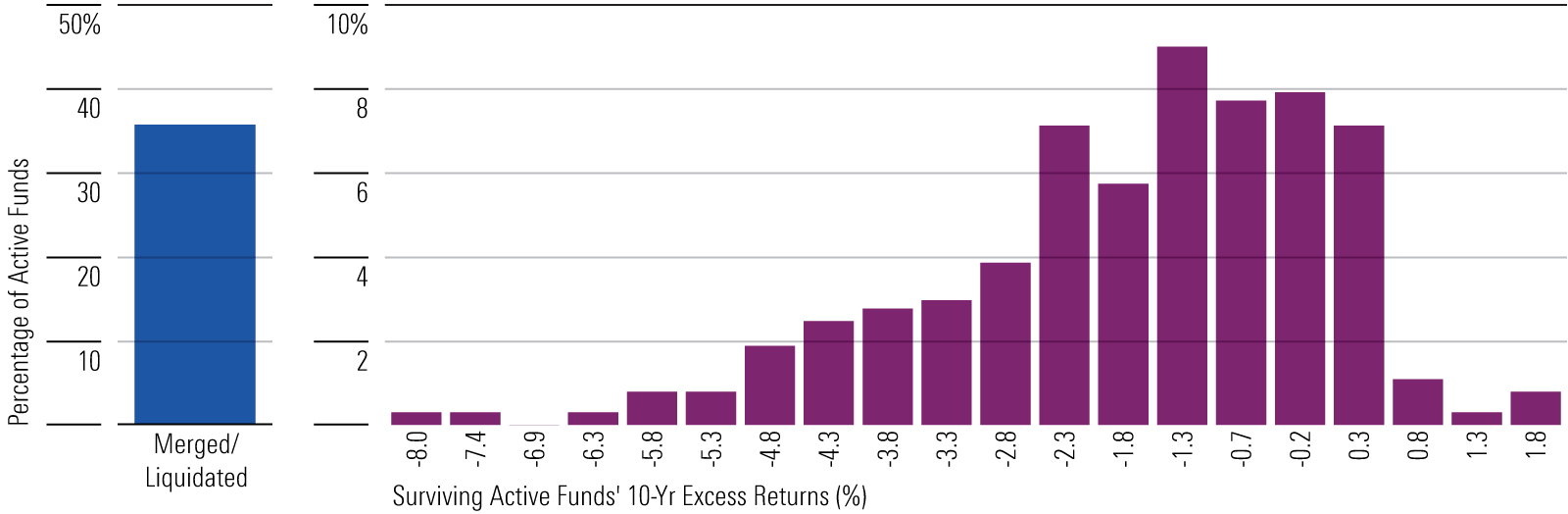

The alpha opportunity is twofold: probability of success and potential payoff (or penalty) of success (failure). Adding this second criterion makes things even more bleak for active managers in US large caps. Not only is success extremely difficult to come by over the long term, but also the potential reward for picking the right active manager is small, while the penalty for getting it wrong can be huge.

The following chart shows the 10-year excess returns by active funds versus the average passive fund in the US large-blend Morningstar Category. Ouch.

The distribution of excess returns by active emerging-markets funds is more palatable for investors. Likewise for bonds. And they look downright promising in real estate categories. Unfortunately, ETFs may not be best suited for some of these lower-capacity markets.

The Market Maker Dilemma

ETF providers need to entice market makers to trade because their trading activity plays a key role in keeping an ETF’s price in line with the value of its portfolio. They prevent ETF share prices from deviating too far from an ETF’s net asset value, and they can help maintain tight bid-ask spreads. A breakdown of either can increase investor costs.

A market maker’s goal is to buy and sell roughly the same risk exposure for a profit. They don’t care if they’re making small gains so long as they can do it again and again. ETF providers keep market makers interested in these trades by making their portfolios easy to hedge. Market makers can make tight markets and arbitrage dislocations quickly when they can easily transfer risk. Typically, that means ETFs should hold stocks or bonds that are easy to trade and/or provide portfolios that are easy to create and redeem in-kind.

Obscure holdings, multi-asset portfolios, and highly differentiated strategies all make it hard for market makers to hedge that risk with precision. That means a lower probability for them to earn a profit, which pushes bid-ask spreads wider and allows for deeper dislocations before they step in to rectify them.

Water Finds Its Own Level

Given ETFs’ capacity concerns, it’s no surprise then that 74% of active US stock ETFs are parked in large-cap categories. Large-cap stocks can handle “Champagne problems” (a term I stole from an asset manager describing the risk of having a too-successful ETF). In comparison, just 53% of active US stock mutual funds are in large-cap categories.

Does this defeat the purpose of going active in ETFs? To an extent, yes. At least according to the Barometer.

But the biggest hurdle facing active managers is cost. Active ETFs tend to charge lower fees than active mutual funds. And active ETFs with substantial flows can use creations and redemptions to build their portfolios, gain tax efficiency, and effectively transfer trading costs to market makers. Whether this is enough for active managers to surpass passives in large-cap stocks or elsewhere remains to be seen.

In other words, cheap, tax-efficient active ETFs may buck the long-term trend of underperforming passives. They should outperform similar active mutual funds at a minimum.

Active Risk Caveat

Generalizations about active funds’ success rates and capacity constraints do not apply to all active ETFs. Funds fall on a risk spectrum. Actively managed ETFs vary from indexlike to highly differentiated from the market. Dimensional and Avantis are great examples of ETF providers that use a systematic active investing approach that looks more like an index than a discretionary manager. These types of ETFs can channel the benefits of passive investing in large caps and avoid the pitfalls of active ETFs in niche markets because of their diversified portfolios. It’s partly why we rate them and their ETFs so highly. Investors can safely sock away hard-earned money in broadly diversified strategies without fear of capacity issues.

Finding the Right Active ETFs

ETFs with capacity concerns often come with wider bid-ask spreads, so investors can look for common characteristics to steer clear of both ills.

Underlying Market

ETFs built around US large-cap stocks usually don’t have these concerns. Investors should be wary of those focused on small caps, emerging-markets stocks, and sector-specific strategies. Narrowing the pool of stocks increases capacity risk and trading costs, like ETFs that only hold technology stocks or real estate.

Portfolio Complexity

Multi-asset ETFs force market makers to hedge both stocks and bonds simultaneously, adding complexity (that is, uncertainty) to the hedging process. In fixed income, high-yield and municipal bonds trade infrequently, forcing market makers to decide whether dislocations are real or caused by a stale valuation. Market makers need a wider spread or larger dislocation to make up for these less reliable profits.

Broad portfolios of easy attainable stocks, Treasuries, or short-term bonds are easily hedged and give market makers leeway to tighten their bid-ask spread and compete over fractions of a penny of profit per share.

ETF Volume and Size

High trading volume is a sign of a healthy ETF and generally indicates trading costs should be lower for investors. High trading volume draws in market makers like moths to flame because more trading means more profits. Active ETFs with solid trading volume are a sure bet to keep market makers engaged. Low-volume ETFs or those with lumpy flows, like buffer ETFs, for example, force market makers to trade more conservatively to ensure those trades remain profitable. That translates into wider spreads and more costly trades for investors.

ETFs with substantial net assets are another sign of health, and large ETFs are often intertwined with trading more frequently. However, investors should make sure the ETF’s size stays proportional to the stocks or bonds it holds. In 2021, ARK Innovation ETF ARKK managed $28 billion despite over half of the stocks in its concentrated portfolio being small or mid-caps. Manager Cathie Wood had Champagne problems, but ARK Innovation ETF investors ended up with the hangover.

Morningstar Medalists

Analyst-driven Morningstar Medalist Ratings have been thoroughly vetted by Morningstar’s manager research team. An ETF’s capacity and liquidity are top of mind when we rate it, active or passive. Investors will find safe passage with any active ETF with a Bronze, Silver, or Gold Medalist Rating and a manager research analyst’s name attached to it.

This article appeared in the August issue of Morningstar ETF Investor. Click here for a free sample issue.

Nguồn: https://nullhypothesis.cfd

Danh mục: News